Once in a while, you just have that moment, that lesson as a teacher that makes you so happy to be in the presence of insightful and caring students. Sometimes these moments fall early on the year, and change the tenor of a class; less frequently they might arrive at the end of the year, just when you think students have checked out and are ready to move on.

This moment for me came after a year of significant focus on issues of diversity and equity. Given a chance to do a year of professional development with a cohort of teachers to examine our own and our school’s practices with diversity and equity, I jumped at the chance and quickly worked hard to put into practice what I learned every month or so.

I changed the lens through which I examined my curriculum and made as many changes as I could. New books showing new perspectives. Lessons critically examining the words and information included (and not included) in our social studies textbook. Working hard to set a careful tone of respectful and open class dialogue.

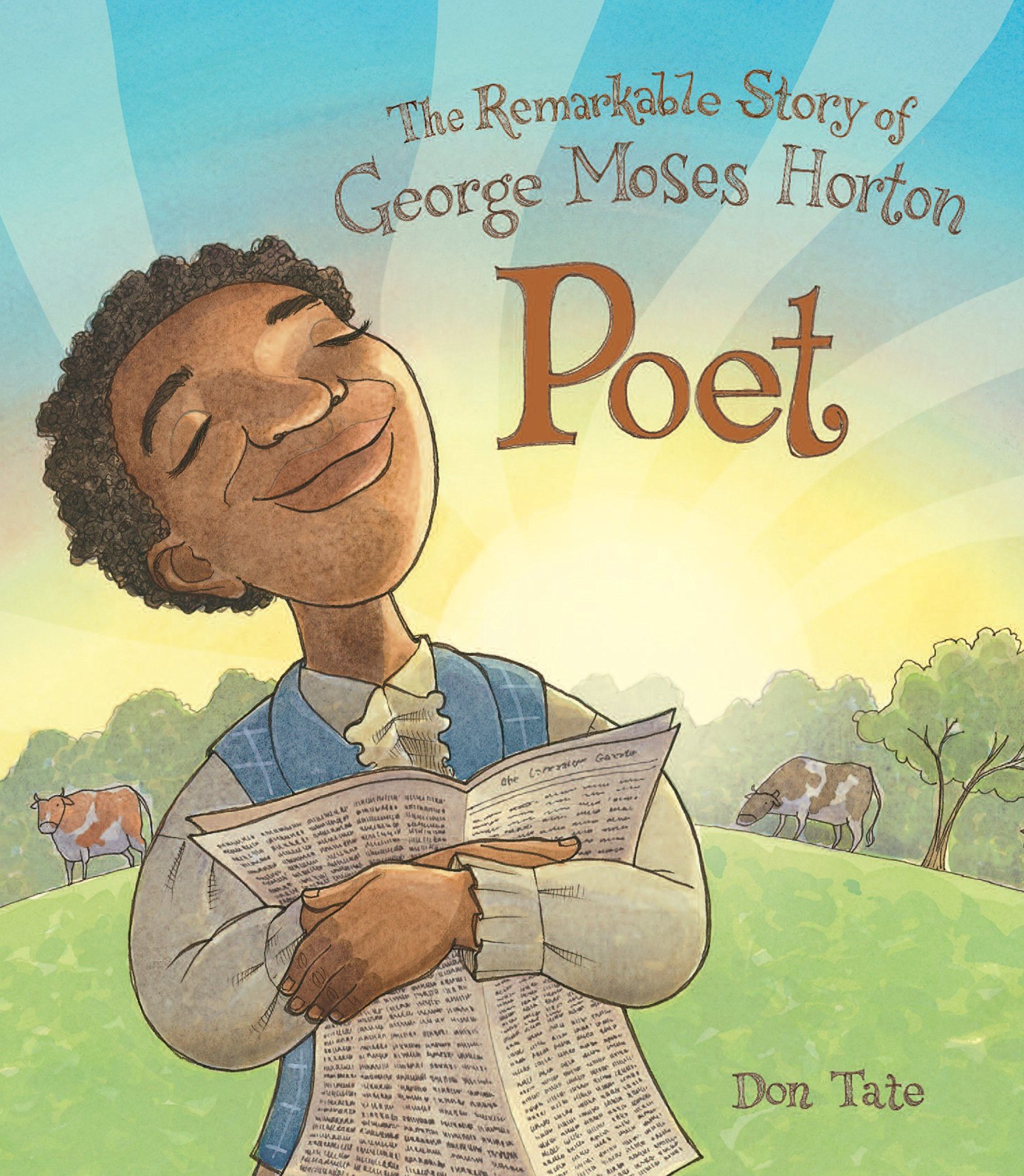

In the perfect storm of a Monday afternoon social studies block, this all came together. We had just read through Don Tate’s wonderful picture book about George Moses Horton, one of the first published African American poets and writers in the South before the Civil War. Horton, who was enslaved, taught himself to read and write and then used his prodigious talent to get paid for his writing, meaning he could have some semblance of freedom working and writing and living on his own most of the time, even though he remained enslaved.

The book is exactly the incredible story that encourages discussion, but it was not until each student read and annotated Tate’s brilliant author’s note that the discussion really went to an entirely different level. Writing about his own experience as an illustrator and author, Tate describes how he was reluctant early in his career to take on books about slavery. He felt he learned about this and only this topic growing up. As a result, he felt ashamed of his heritage. It took years, he writes, to realize the pride in the resilience of other African Americans in the face of almost incomprehensible cruelty.

My students were fascinated by his admissions as a writer and we dove into the complex nature of what it means to be black, or white, or brown, or Jewish, or female and learn about difficult issues in history. My students wanted to know why Tate was “the only brown face in a sea of white.” One student chillingly recounted a documentary he saw where a black student explained that his teacher had turned to him every time the topic of slavery came up in class to explain for everyone else what it was like, no matter that the boy was not alive at that time and had no more knowledge of the terrible institution than any other student in that class.

We wondered why “white kids snickered and made jokes about [slavery]” and why, as Tate adds, “Sometimes, black kids did too.” In four successive answers, students explained that: 1) perhaps it was because these students Tate mentioned were uncomfortable talking about a difficult topic; 2) that perhaps these students did not fully understand or were learning about it for the first time; 3) that perhaps it showed that students “really felt bad about history and almost it made them feel badly about themselves” (leading into a brief discussion of internalized oppression); and 4) that perhaps these students did what a lot of people do, which is go along with one person being mean or inappropriate. The class dialogue continued as we made connections to this article and the discussions we’ve had around antisemitism and the treatment of Jews in WWII during our reading of Number the Stars.

Finally, when we read Tate write: “But as I read the stories and studied the history of my people, I had a change of heart. I decided that there was nothing to be ashamed of, and much to feel proud about.” We all observed the new bookshelf that I put together and we noticed the different topics, many of them involving tough times in history, but many also involving an inspiring story about an essential world leader like Nelson Mandela or the ingenuity of one young boy in Malawi to build windmills and help his family survive. We looked at a portrait of Sonia Sotomayor and then considered how Freedom over me shows many perspectives on what it might have been like to be enslaved, and that, of course, every person who went through this experience showed inconceivable resilience by dreaming of a better time ahead or for their children and also the pride in having a skill and a trade and to feel important.

The conversation took an hour and we covered four paragraphs. Yet I got choked up thinking about the empathy and attentiveness with which my fourth grade class went about these often terrible, incredibly complex discussions. I was delighted to hear the voices of a number of students who typically shy away from conversation but who raised their voice powerfully to demonstrate what meaningful and kind thinking looks like.

In the second column of the author’s note, and then on the second page, there are plenty of other fascinating issues to dig into: how education in general and literacy in particular can be a tool wielded to fight back against injustice, how the institution of slavery looked a bit different at different times and in different places, as Tate discovered researching about Horton’s life in North Carolina, and the other works authored by a tremendous author and poet, someone who deserves to be known about and read, precisely because of his circumstances AND no matter his circumstances. As always with teaching and learning, there remains more to do.