Throughout our history, people have fought for the right to vote. In 2020, much like in years past, voting rights cannot be taken for granted. How do we teach kids about expressing their voices, prepare them to become the voters of the future, and help them to see ways they can take action right now?

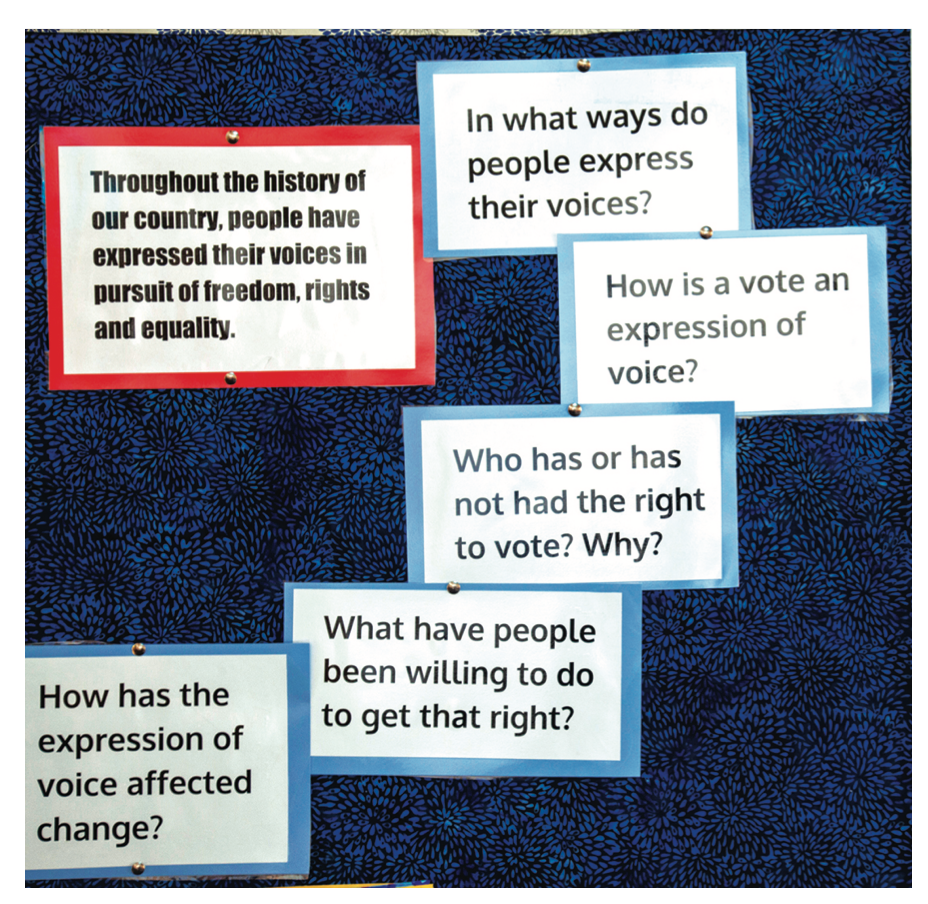

These essential questions guide this inquiry

We begin with essential questions about voice, voting, and the history of the struggle for voting rights. We ask students to consider:

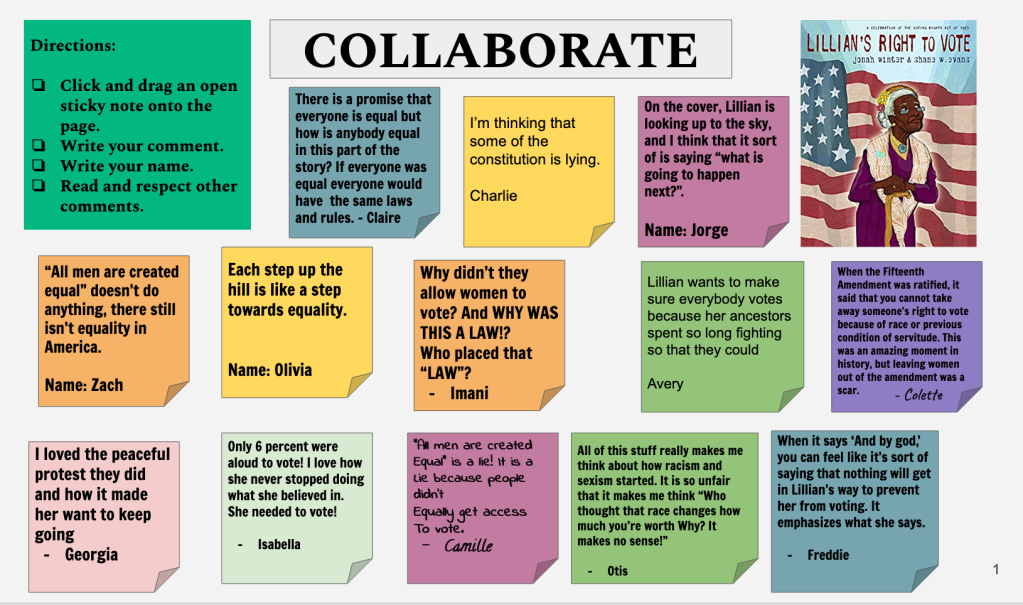

Students read a variety of picture books and then break into small groups to discuss them. They respond on a shared Padlet or other interactive tools like the shared Google Slide below.

Digital sticky notes

Students leave tracks of their thinking with digital sticky notes on a shared Google Slide.

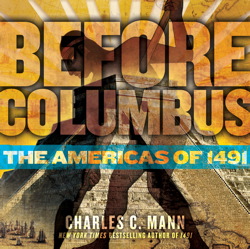

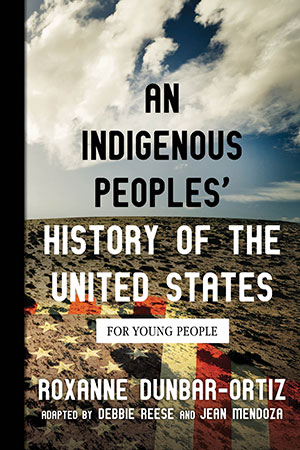

Resources

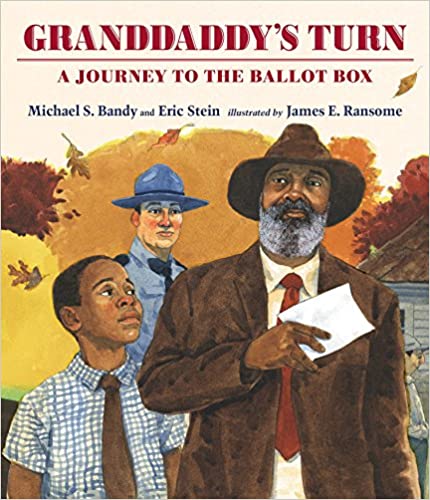

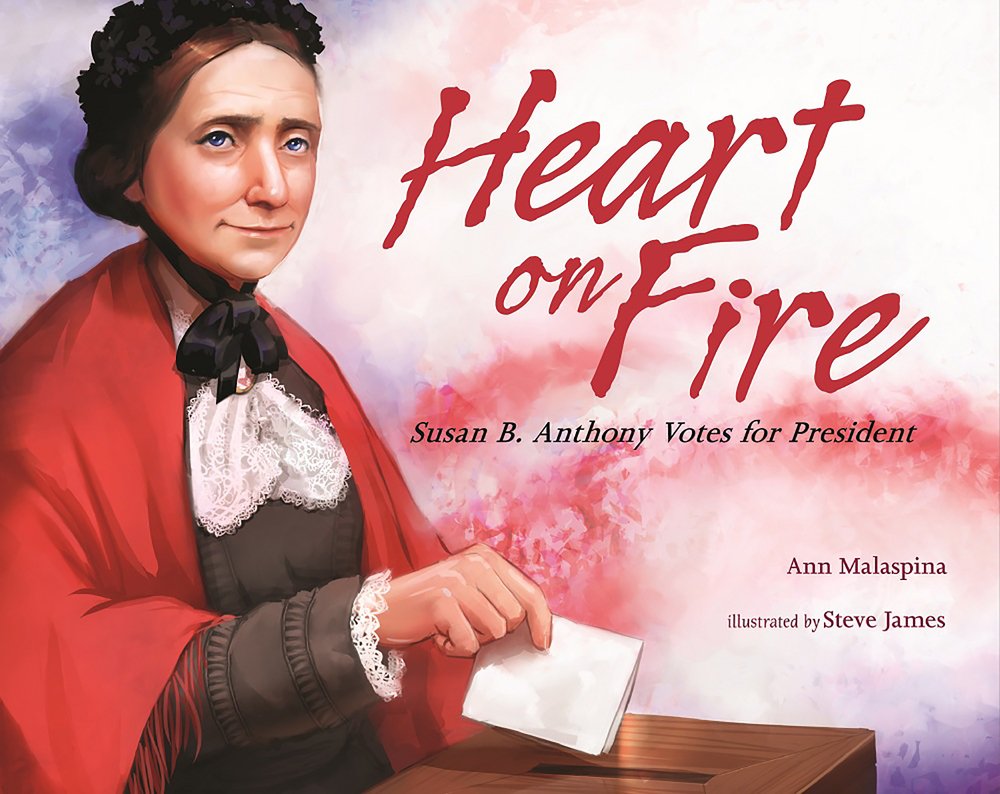

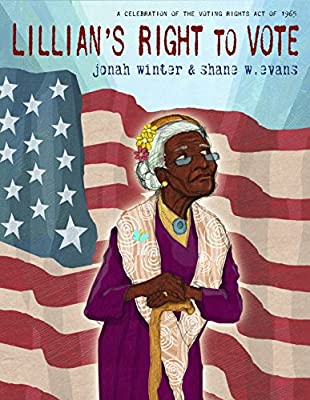

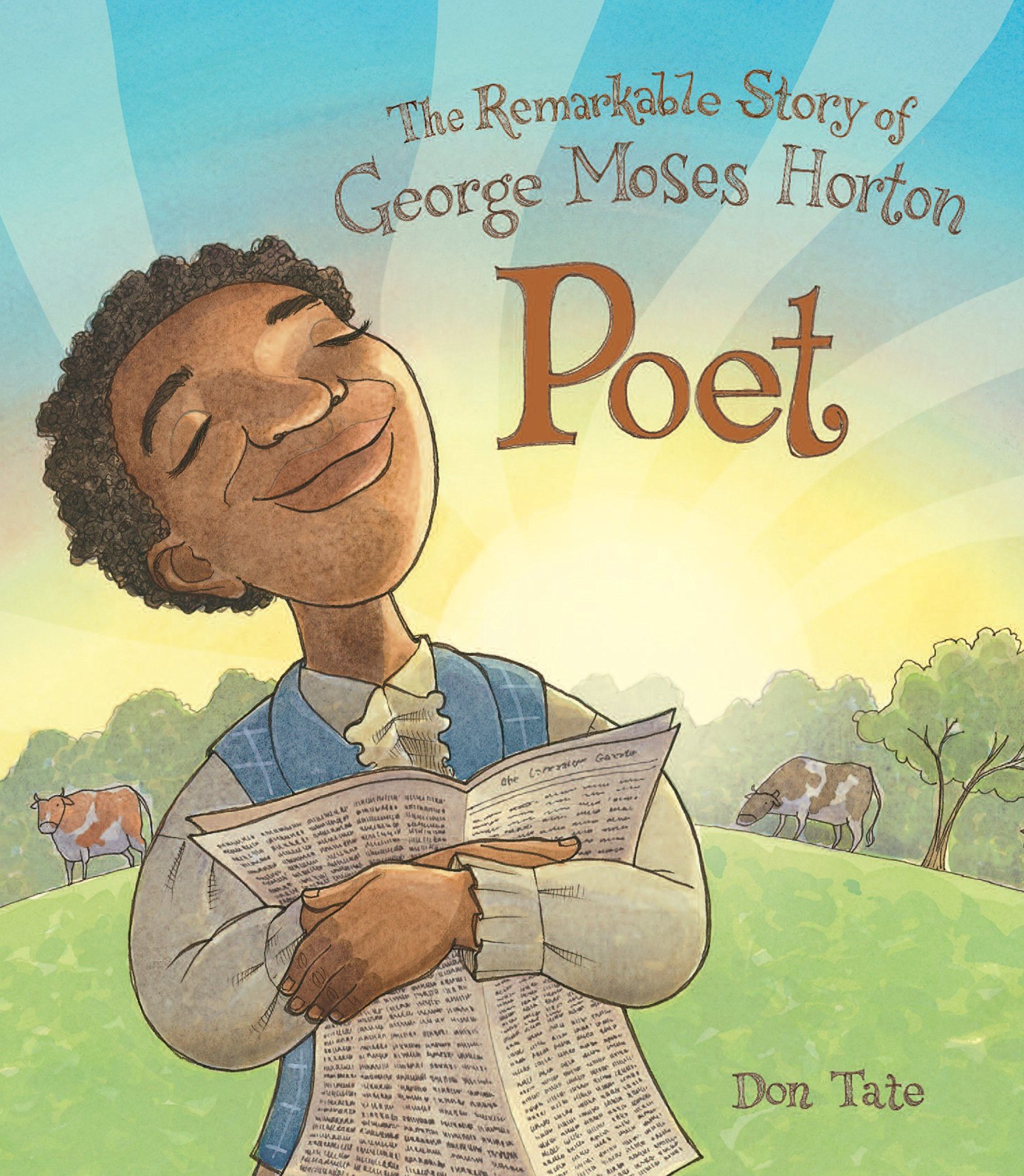

Picture books like these, as well as other resources like the ones listed below, engage students and help them learn about voting issues throughout history. These stories highlight how people have fought for the right to vote.

Selma: The Bridge to the Ballot

Videos such as Selma: the Bridge to the Ballot (Teaching Tolerance) immerse kids in the struggle for voting rights in the 1960s.

The Split History of the Women’s Suffrage Movement

Historical sources such as The Split History of the Women’s Suffrage Movement provide different perspectives on women’s lack of equal rights in the later 19th and early 20th centuries.

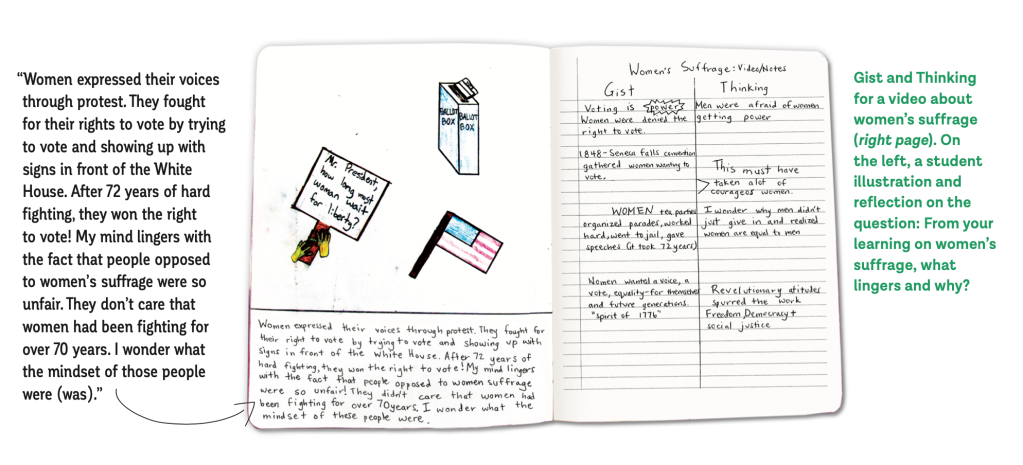

Students respond to these resources in their notebooks. They use a Gist / Thinking scaffold to learn synthesize new information and respond with their thoughts and questions. Their illustrations highlight the important ideas in the books and videos they view and read.

Once students build up a strong knowledge base, the class can demonstrate their understanding by creating a timeline of the history of voting rights. Other aspects of voting rights history can be researched in depth, like the Chinese Exclusion Act that barred Chinese immigrants from voting, or the steps taken through U.S. history to keep Native Americans from participating in government. Here is an example of a shared Padlet page where students contributed posts to a voting rights timeline. Teachers can model by adding initial posts and students do further research before adding their own.

Taking Action

Eventually, students may want to take action. Connect with a nearby high school or college so younger students can encourage older students to register or vote, perhaps for the first time. Connect with local organizations that are sharing information about voting during the pandemic or reminding citizens of voter ID laws in their state.

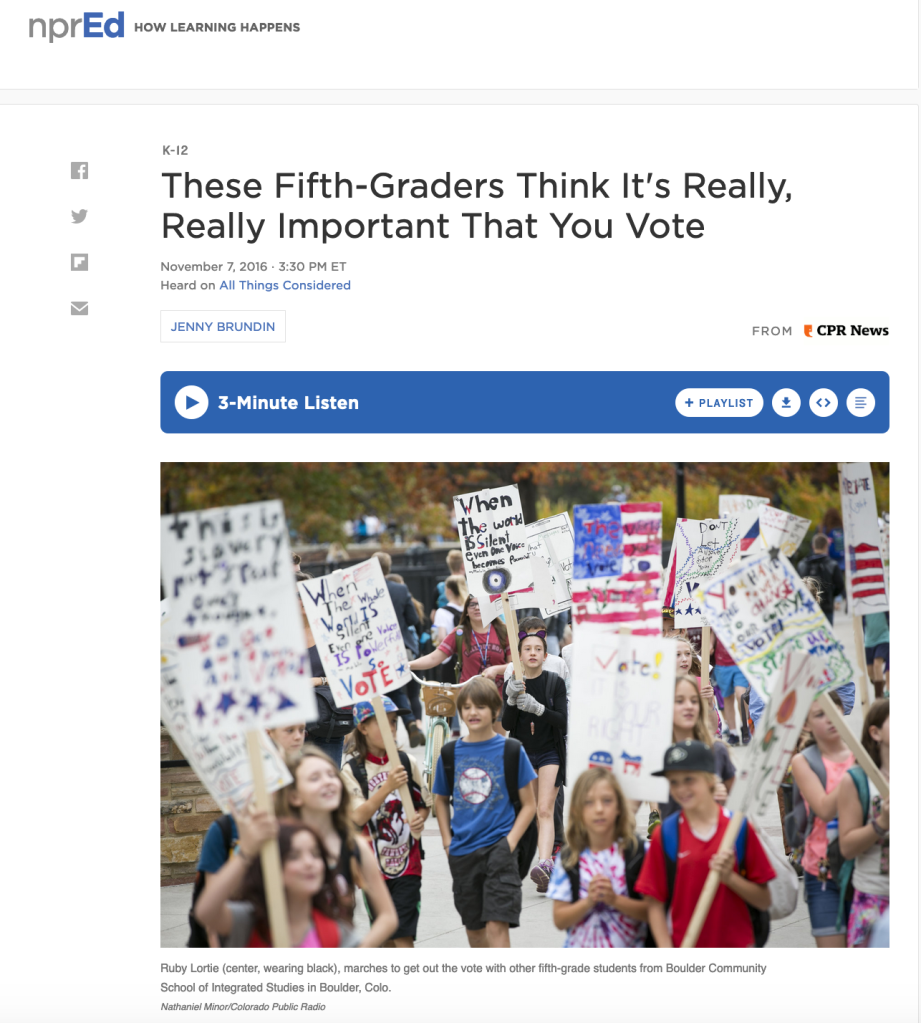

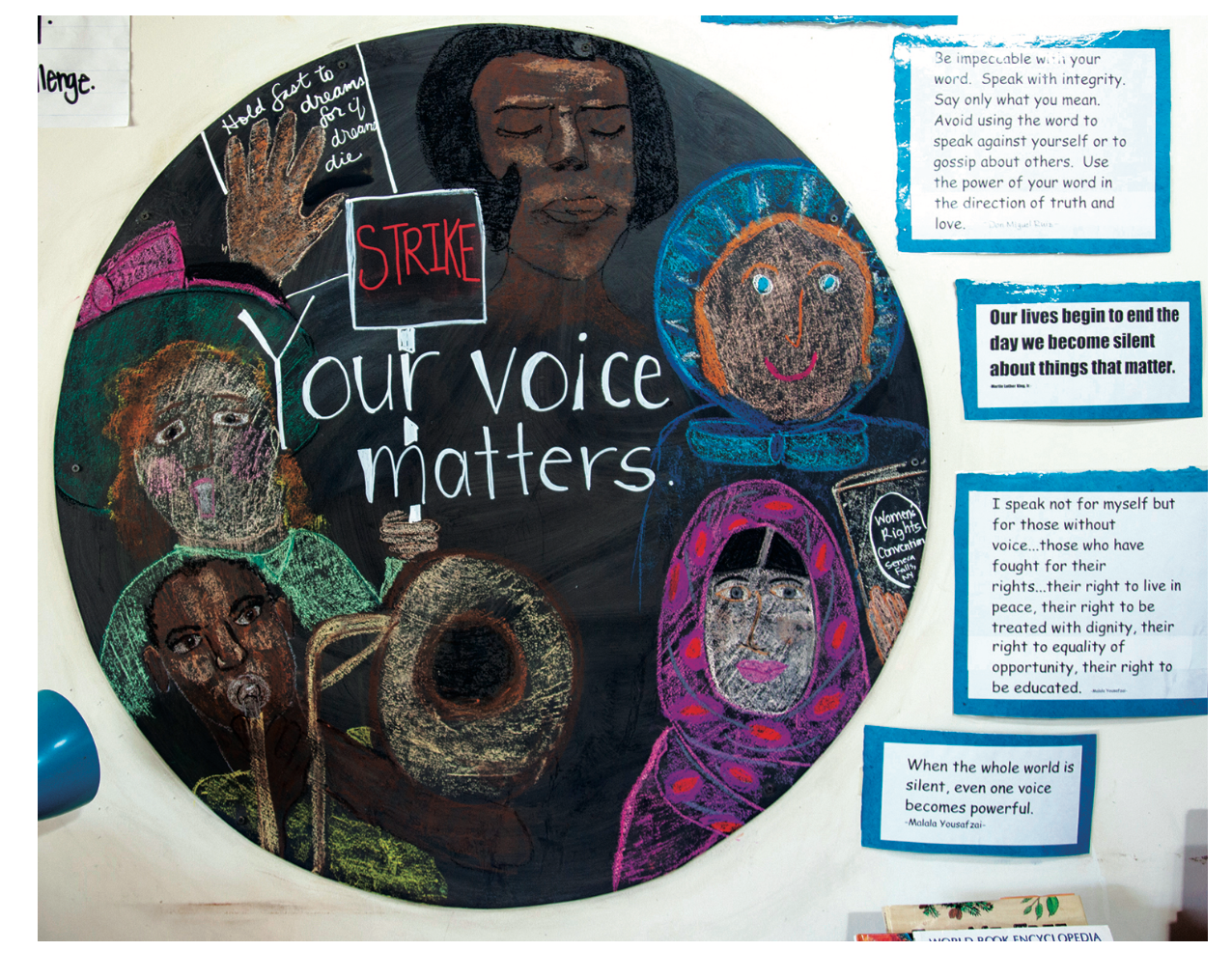

Students can research different ways to help get out the vote, like Karen Halverson’s class of 5th graders did. They created posters and placards, realizing they could take their persuasive messages to a nearby university campus to encourage students there to vote.